John C. McLoughlin's Archosauria was published in 1979 by the Viking Press and was, let's be fair here, RIDICULOUSLY ahead of it's time. He includes some fine pointillism illustrations. He is also one of the first people to depict most of his small theropods with fluffy feathers:

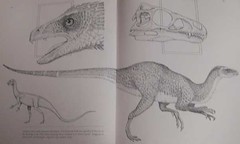

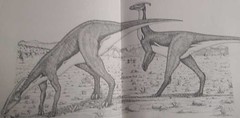

These Coelurus drawings are my favorites in the book. The detail is lovely. I like the hawklike facial study in the upper-left corner (though I'm not sure how accurate it is given modern evidence). And I especially like how McLoughlin includes a copy of an old illustration of each animal, as he does in the lower-left here.

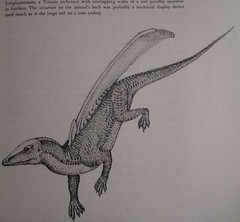

McLoughlin briefly covers other members of the Archosaur... group...? (Someday I will post my Rant Against Linnaeus' Classification System.) One of these is little Longisquama (here, called Longisquamata):

Here McLoughlin gives us one of the reasons why his book is notorious: he is perhaps best known for having some... interesting ideas about prehistoric animal anatomy and behavior. Longisquama, according to McLoughlin, had only one set of those... things on his back. And he used them to trap warm air pockets for insulation. And they are, without doubt, the predecessors of feathers.

I almost hate to say that

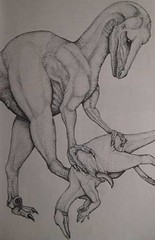

It's also very strange that Coelurus, Longisquama, Saltopus, and other animals of that ilk all sport a fine coat of feathers - and Deinonychus doesn't. In fact, McLoughlin's Deinonychus is just weird all around:

Something tells me that this wouldn't work...

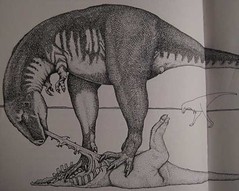

Now, to be fair, there weren't many complete fossils of dromeosaurs back in 1979. There weren't many good complete fossils of tyrannosaurs either, which goes a way in explaining Sharkface McDerpasaurus rex here:

Uh... yeah.

Old dinosaur books, as we have seen, depict all hadrosaurs as swimming swamp-dwellers. McLoughlin instead depicts them, more accurately, as upland animals more akin to a really big cow than a really big duck. That said, take a look at his Parasaurolophus couple:

It's good that they're not up to their balls in a swamp, but this might be too far in the opposite direction, and we all know we ought to avoid that. :)

Next is one of the most unintentionally hilarious drawings in the book:

I am in love with this drawing. You can't not love an animal that defends himself by lying down. Good jarb, Spike! You just exposed your tasty flank!

Now, if you are reading this and you've already heard of John McLoughlin, then you know what I've saved for last. If this is the first time you've heard of him, boy are you in for a treat.

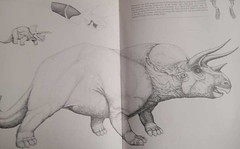

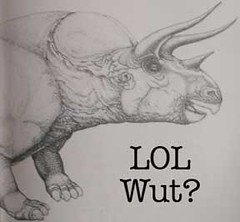

I said, and showed, that McLoughlin had some VERY unusual theories on dinosaur anatomy. None of them are as mind-bending as what follows. Ladies and gentlemen, John McLoughlin's reconstruction of Triceratops:

Take a minute or two. Let it allllll sink in.

OK? Well, here are some other ceratopsians:

I do enjoy this paragraph that ends the Ceratopsian chapter, just because it's such a great mental image (click for big):

More, and better, has been written about this theory at good old Tetrapod Zoology. It's not really surprising that this has since been debunked (essentially for just plain not working). That poor Styracosaur looks to be in pain.

Now while we're on the subject of people with weird ideas about prehistoric animals, I wonder if David Peters has ever written a book...

Addendum: There is something McLoughlin-y in the water, it seems.

Certainly, read the Other Branch post, because I won't be able to keep from spoiling that McLoughlin also thought that archosaurs were like Wolverine.

----

Art of the day! Speaking of odd-looking dinosaurs (although ones that look odd anyway no matter who reconstructs them), here is Concavenator!